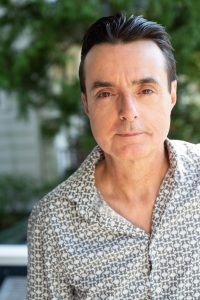

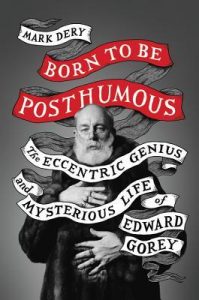

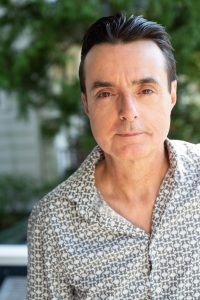

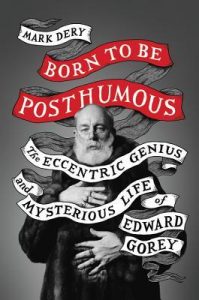

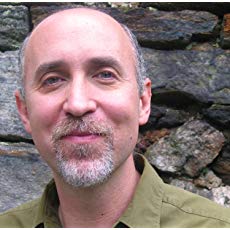

Mark promoted his Edward Gorey biography Born to Be Posthumous on Twitter and I politely asked for a copy to review. He graciously offered publisher contact information, and Little, Brown, & Company sent me a copy. It’s so good, people. If you’re not familiar with Gorey’s work, you will want to be in on this open secret after reading Dery’s book. Gorey was a fascinating character, and Dery is a brilliant storyteller. He’s really so much more—this interview a tiny peek into the profundity of his work, but I’ll let you read up on Mark further on his own website. Links to connect with Mark and purchase his work follow the interview.

Mark promoted his Edward Gorey biography Born to Be Posthumous on Twitter and I politely asked for a copy to review. He graciously offered publisher contact information, and Little, Brown, & Company sent me a copy. It’s so good, people. If you’re not familiar with Gorey’s work, you will want to be in on this open secret after reading Dery’s book. Gorey was a fascinating character, and Dery is a brilliant storyteller. He’s really so much more—this interview a tiny peek into the profundity of his work, but I’ll let you read up on Mark further on his own website. Links to connect with Mark and purchase his work follow the interview.

Tell me about your writing process: schedule, environment, strategies, inspirations intangible and material, magic spells, etc.

Tell me about your writing process: schedule, environment, strategies, inspirations intangible and material, magic spells, etc.

I rise at the crack of noon, as Christopher Hitchens liked to say, and lower myself into a vat of virgins’ blood in strict adherence to Elizabeth Báthory’s beauty regimen for eternal youth. After a rejuvenating soak, I trim the topiary; then spend the morning in bed, languidly leafing through the Encyclopedia of Unimaginable Customs and nibbling candied violets.

But seriously: I have no set schedule unless I’m on assignment—working on a lecture, knocking off a piece of journalism, or writing a book, as I have been for the past seven years.

My “environment”—why am I thinking of a hermit crab in a terrarium?—is a small office in the attic of my house, a worse-for-wear 1868 Victorian in New York’s Lower Hudson Valley. It’s the proverbial garret, snug as a fo’c’sle, or what I imagine a fo’c’sle would feel like, based on second-grade memories of books about pirates and whaling. On top of one of my bookshelves is what I like to call my aesthete’s altar, a poor man’s cabinet of curiosities: a pickled Jerusalem Cricket floating in formalin, a desiccated Tarantula Hawk, postcards of my pantheon of secular saints—E.A. Poe, Oscar Wilde—and of images from my personal symbology (Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley, that Diane Arbus photo of identical twins) and, for crowning effect, two human skulls. Which makes it sound more romantic than it is: the paint on the walls nearest my desk is scabrous; teetering stacks of whatever books I’m using for my research are heaped on every available surface, including the floor surrounding my desk, which makes the passage from desk to door tricky at best and perilous at worst. When I’m in the death throes of an essay or a book chapter, things can get seriously out of hand, with xeroxes of articles and books propped open to specific pages threatening to avalanche off my desk, which they often do. Inspiration? That comes from the subject at hand, whatever it is, but if inspiration is lacking, a heart-hammering cup of Bustelo—three scoops of espresso made in my battle-tested Bialetti Moka—never fails to beckon the muse. I’m one of those writers who listens to music while he works, instrumental only (words are too distracting), preferably something that suits the mood of whatever I’m working on, though not necessarily in a strictly literal way. For Gorey, that could be anything from Morton Feldman to Jóhann Jóhannsson’s soundtrack for Arrival to György Ligeti’s “Études for Piano” to No Pussyfooting by Fripp and Eno. By five o’clock, I’ve had two pots of Bustelo and need to chase the evil spirits out of my head. A bike ride or a run along the tree-lined streets at the woodsier end of town are just what the doctor ordered; deer are everywhere, browsing on suburban shrubs, and the trees look uncanny in the oncoming twilight, branches clawing at the sky. (My iPhone is full of photos of trees that look like something out of Algernon Blackwood’s gothic tales of haunted forests.) Then it’s home for dinner, typically spent yelling at cable news, then back to my lair for a few hundred more hard-won words, with a glass of shiraz to downshift after my heavily caffeinated day.

How do you choose your subjects?

How do you choose your subjects?

They choose me. I have the attention span of a gnat, which is good for the mind but bad for the wallet, since hoeing the same row is more lucrative than being an intellectual flâneur. One subject leads me to another, through some combination of serendipity and free-association. In an age of hyperspecialization, being a generalist isn’t a recipe for success but the idea of fitting your mind to a monorail seems like living death. I had a colleague once, a journalism pundit, who told an interviewer (with suitable portentousness), “I get up every day and ask myself one question: What are journalists for?” Just shoot me, I thought.

Talk about your support system online and IRL; what motivates you? Who are your biggest cheerleaders?

Talk about your support system online and IRL; what motivates you? Who are your biggest cheerleaders?

In all honesty, I don’t look for support, at least not in the sense you seem to mean—a kind of validation. Do most writers? I suspect not. Writers write not because they want to write but because they must; it’s not what they do but who they are. Certainly, fan mail is balm to the soul, not to mention a bracing antidote to that nasty review that made you want to inch out onto the window ledge—or drop a cornice on the offending critic. That said, I write for The Ideal Reader, a vaguely defined apparition who should never be brought into sharp focus but who bears a striking resemblance, I have a sneaking suspicion, to the face in the shaving mirror. Few writers admit it, but most write for themselves. Of course, you have to divide yourself by The Other—your wider audience—to save yourself from a fatal self-indulgence, not to mention abject poverty, which is where editors are very writer’s saving grace. Mine, Michael Szczerban at Little, Brown, saved me from a million little misdemeanors and a few Class A felonies in my Gorey biography. Writing is a communicative act, to be sure, unless you’re writing a diary, the point of which has always eluded me: there’s no paycheck, and no applause. At the same time, a good writer is his own severest critic and thus his most honest reader—maybe not the only support system he needs, but certainly the linchpin of the thing. As Lou Reed snarls in his onstage rant, on Take No Prisoners, about the rock critic John Rockwell, “I don’t need you to tell me that I’m good.”

As a writer and public speaker, how does your life influence your work and vice versa?

As a writer and public speaker, how does your life influence your work and vice versa?

It doesn’t. Lecturing is to writing as improvisation is to composing, I suppose. I speak from written texts but, in the run-up to my talk, annotate them with frantically scribbled marginalia, jotted notes for fruitful digressions inspired by keywords in the text. They’re a kind of musical notation, indicating where to wander off into the weeds and when to double back to the main arc of the argument or narrative. Sometimes, ideas generated in this manner will find their way into a revised version of the essay or book chapter or whatever it is; so, too, will comments and questions from the audience. But I’m enough of a control freak that I almost never speak completely extempore. At the same time, I’d never think of just reading my text, as academics tend to; it’s pure chloroform, calculated to send the audience streaming to the exits in the first 10 minutes!

What do you love most about your creativity?

What do you love most about your creativity?

That it opens the door to The Marvelous, as the surrealists called it. As a practicing surrealist, I’m always on the lookout for The Marvelous—the uncanny, the fantastic, the utterly alien lurking just around the corner, hidden in the everyday, but only revealed when seen from a certain angle. Gorey was fond of quoting two quotes that were, he said, at the heart of his worldview. One of them was from the surrealist poet Paul Éluard: “There is another world but it is this one.” The other was from the Oulipo author Raymond Queneau: “Things aren’t as they seem, but they aren’t anything else, either” (or words to that effect). Where those two realities flow together is where I fish, as a writer.

Connect with Mark:

Connect with Mark:

website

Twitter

Amazon

Goodreads

The Daily Beast

Hyperallergic

Thought Catalog

boing boing

Mark promoted his Edward Gorey biography Born to Be Posthumous on Twitter and I politely asked for a copy to review. He graciously offered publisher contact information, and Little, Brown, & Company sent me a copy. It’s so good, people. If you’re not familiar with Gorey’s work, you will want to be in on this open secret after reading Dery’s book. Gorey was a fascinating character, and Dery is a brilliant storyteller. He’s really so much more—this interview a tiny peek into the profundity of his work, but I’ll let you read up on Mark further on his own website. Links to connect with Mark and purchase his work follow the interview.

Mark promoted his Edward Gorey biography Born to Be Posthumous on Twitter and I politely asked for a copy to review. He graciously offered publisher contact information, and Little, Brown, & Company sent me a copy. It’s so good, people. If you’re not familiar with Gorey’s work, you will want to be in on this open secret after reading Dery’s book. Gorey was a fascinating character, and Dery is a brilliant storyteller. He’s really so much more—this interview a tiny peek into the profundity of his work, but I’ll let you read up on Mark further on his own website. Links to connect with Mark and purchase his work follow the interview. Tell me about your writing process: schedule, environment, strategies, inspirations intangible and material, magic spells, etc.

Tell me about your writing process: schedule, environment, strategies, inspirations intangible and material, magic spells, etc.  How do you choose your subjects?

How do you choose your subjects? Talk about your support system online and IRL; what motivates you? Who are your biggest cheerleaders?

Talk about your support system online and IRL; what motivates you? Who are your biggest cheerleaders? As a writer and public speaker, how does your life influence your work and vice versa?

As a writer and public speaker, how does your life influence your work and vice versa? What do you love most about your creativity?

What do you love most about your creativity? Connect with Mark:

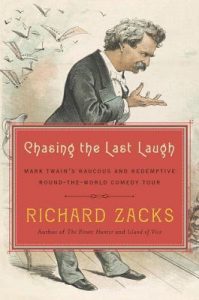

Connect with Mark: Richard Zacks was born in Savannah, Georgia, but grew up in New York City. As a teenager, he gambled on the horses, played blackjack in illegal Manhattan card parlors, and bought his first drink at age 15 at the Plaza Hotel. He studied Arabic in Cairo, Italian in Perugia, and French in the vineyards of France. He wrote a syndicated column for four years carried by the

Richard Zacks was born in Savannah, Georgia, but grew up in New York City. As a teenager, he gambled on the horses, played blackjack in illegal Manhattan card parlors, and bought his first drink at age 15 at the Plaza Hotel. He studied Arabic in Cairo, Italian in Perugia, and French in the vineyards of France. He wrote a syndicated column for four years carried by the Books come in phases. I love the research. It plays to my voyeuristic/private eye tendencies. I love snooping into lives in the past, reading personal letters, trying to build out entire scenes. Since I was trained as a journalist before becoming a historian, I lean hard towards Who, What, When and Where. I want physical details, so I build elaborate timelines, sometimes 400 pages long… Aug. 22, 1893, Aug. 24, 1894… and then I layer in every detail I can find with its source. Over time, these random details accumulate and a clear picture of many individual days starts to emerge. This format of a giant timeline helps with “plotting” the non-fiction narrative. Yes, it is non-fiction, but writers have huge choices as to structure and I always want to build a plot and suspense, because that’s what I need as a reader to keep me interested.

Books come in phases. I love the research. It plays to my voyeuristic/private eye tendencies. I love snooping into lives in the past, reading personal letters, trying to build out entire scenes. Since I was trained as a journalist before becoming a historian, I lean hard towards Who, What, When and Where. I want physical details, so I build elaborate timelines, sometimes 400 pages long… Aug. 22, 1893, Aug. 24, 1894… and then I layer in every detail I can find with its source. Over time, these random details accumulate and a clear picture of many individual days starts to emerge. This format of a giant timeline helps with “plotting” the non-fiction narrative. Yes, it is non-fiction, but writers have huge choices as to structure and I always want to build a plot and suspense, because that’s what I need as a reader to keep me interested.  A friend described his publishing process as “the calm before the calm.” Thankfully, I have never experienced that. The PR departments of the various publishers have gotten me piles of radio interviews over the years and bookstores appearances. I LOVE giving my PowerPoints, especially this last one on Twain, since it generated lots of laughs. I never knew how absolutely glorious it feels to make two hundred people laugh. Thank you, St. Louis.

A friend described his publishing process as “the calm before the calm.” Thankfully, I have never experienced that. The PR departments of the various publishers have gotten me piles of radio interviews over the years and bookstores appearances. I LOVE giving my PowerPoints, especially this last one on Twain, since it generated lots of laughs. I never knew how absolutely glorious it feels to make two hundred people laugh. Thank you, St. Louis. My wife is a literary agent, so she reads the near-final draft. She is brutally honest, after I convince her yet again that I want to be brutally honest. I try not to bother her too much, but she is really good at what she does, and has dozens of paying clients to serve. Reviews have been solidly positive over the years, but I did get a complete slam in one major publication. I was flabbergasted. I complained to the book editor and he asked whether I believed in freedom of the press and of opinions. I said “Sure,” but that he shouldn’t let children play with matches. I also like Ben Franklin’s line about Freedom of the Press being accompanied by Freedom of the Cudgel. Ka-boom.

My wife is a literary agent, so she reads the near-final draft. She is brutally honest, after I convince her yet again that I want to be brutally honest. I try not to bother her too much, but she is really good at what she does, and has dozens of paying clients to serve. Reviews have been solidly positive over the years, but I did get a complete slam in one major publication. I was flabbergasted. I complained to the book editor and he asked whether I believed in freedom of the press and of opinions. I said “Sure,” but that he shouldn’t let children play with matches. I also like Ben Franklin’s line about Freedom of the Press being accompanied by Freedom of the Cudgel. Ka-boom.

Connect with Richard Zacks:

Connect with Richard Zacks: I met Bill on Facebook. He’s unique, pragmatic, wryly funny, and shares lots of mushroom pics amongst his politics. Oh yeah, he’s also a pretty talented writer. He’s always surprising me, in his books, online, and here in his interview. Read about his process and creativity; then read his books. You’re welcome.

I met Bill on Facebook. He’s unique, pragmatic, wryly funny, and shares lots of mushroom pics amongst his politics. Oh yeah, he’s also a pretty talented writer. He’s always surprising me, in his books, online, and here in his interview. Read about his process and creativity; then read his books. You’re welcome.

sometimes five or six a day, at any time, like waiting for my daughter at ballet class, just out in the car with the laptop tapping away. I do have a studio and when things get serious I sit out there with the skunks. I do a lot of daydreaming and side reading and more and more social media, unfortunately, or fortunately, I’m not sure which. Politics has clouded my brain, as well, but we can’t sit idly by. I had to look up pantser. I am not a pantser, but draft multiply and give myself all the time in the world.

sometimes five or six a day, at any time, like waiting for my daughter at ballet class, just out in the car with the laptop tapping away. I do have a studio and when things get serious I sit out there with the skunks. I do a lot of daydreaming and side reading and more and more social media, unfortunately, or fortunately, I’m not sure which. Politics has clouded my brain, as well, but we can’t sit idly by. I had to look up pantser. I am not a pantser, but draft multiply and give myself all the time in the world.

send the pages back in and return to the new project. Usually at that point the old project is accepted. Next come copyedits, possibly a legal reading, then first-pass galleys, second-pass galleys, all while a cover is being designed at the publisher’s, and jacket copy being written, a publicity campaign designed, book tour scheduled, all that stuff, which I have little to do with except approval or disapproval. The book comes out, the tour starts, I go on TV and radio, all the while finding those little blocks of time to work on the new project.

send the pages back in and return to the new project. Usually at that point the old project is accepted. Next come copyedits, possibly a legal reading, then first-pass galleys, second-pass galleys, all while a cover is being designed at the publisher’s, and jacket copy being written, a publicity campaign designed, book tour scheduled, all that stuff, which I have little to do with except approval or disapproval. The book comes out, the tour starts, I go on TV and radio, all the while finding those little blocks of time to work on the new project.

I too have an interesting background of employment (including llama care) giving me insight for specific storylines. How has your background prepared you for your writing career, and how does your life influence your art and vice versa?

I too have an interesting background of employment (including llama care) giving me insight for specific storylines. How has your background prepared you for your writing career, and how does your life influence your art and vice versa? What do you love most about your creativity?

What do you love most about your creativity?

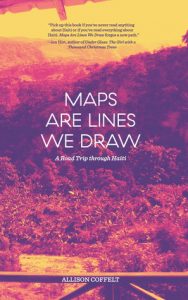

As a blans—not just white, but an outsider—Coffelt does her best to balance her ability to give to a population “there” with an awareness of Haiti’s historical perspective of her “here.” At the risk of symbolizing “the great white hope,” she spends three weeks following Dr. Jean Gardy Marius, founder of OSAPO, Organizasyon Sante Popile (Public Health Organization), plucking gently at the web of (in-)humanity that has created the Haiti of today.

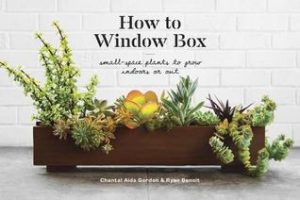

As a blans—not just white, but an outsider—Coffelt does her best to balance her ability to give to a population “there” with an awareness of Haiti’s historical perspective of her “here.” At the risk of symbolizing “the great white hope,” she spends three weeks following Dr. Jean Gardy Marius, founder of OSAPO, Organizasyon Sante Popile (Public Health Organization), plucking gently at the web of (in-)humanity that has created the Haiti of today. This gorgeous, little book begins with a basic introduction to container gardening: aesthetics, placement, sunlight, tools, soil / topping, plant selection, watering, and maintenance. It’s then divided into16 chapters with succinct, descriptive headings, such as Herb Garden, Edible Petals, Southern Belle, and Rain Forest. Each chapter begins with a photo of the finished product and a quick review box of logistics: location, light, window direction, ease of care, soil / topping, water, and feed. Following is a spread of the individual plants with Latin and layman names. Step-by-step instructions have corresponding pictures. At the end, there’s a short chapter on customizing a box and another listing resources.

This gorgeous, little book begins with a basic introduction to container gardening: aesthetics, placement, sunlight, tools, soil / topping, plant selection, watering, and maintenance. It’s then divided into16 chapters with succinct, descriptive headings, such as Herb Garden, Edible Petals, Southern Belle, and Rain Forest. Each chapter begins with a photo of the finished product and a quick review box of logistics: location, light, window direction, ease of care, soil / topping, water, and feed. Following is a spread of the individual plants with Latin and layman names. Step-by-step instructions have corresponding pictures. At the end, there’s a short chapter on customizing a box and another listing resources.