In Brazil, Nazi fugitive Klaus Holland, aka Matheus Esperanca, raises his son by a prostitute with a Jewish kapo from Udenspul, the concentration camp he commanded. The son, Deus, considers the kapo his mother, and after her death, takes mysterious photos from her to a professor in his US university to research his ancestry, where he learns the true identity of his father and the extent of his crimes. Olokita brilliantly uses the concept of god as a measurement of morality, or rather lack of humanity, as Klaus plays God in determining who dies, though his own religious beliefs remain deliciously ambiguous. The character development is so well done that dear reader will be researching names. Although written in third person for everyone else, Klaus is in first person, bringing the reader up close and personal to a man with his own version of right and wrong based on his complete lack of empathy, exploring the idea of how powerful he believes himself. The ending revelation is quite coincidental and is evidenced only by Klaus’ perception, so it’s not clear why it’s readily believed by Deus and his new love Heidi. It’s anti-climactic after the delightful irony of Klaus’ downfall. With so many rumors, legends, and news items, inspiring a plethora of literature, on the Holocaust, this unique story of a fugitive hiding out in South America is a definite must-read. It’s themes rove beyond the simple good vs. evil and the idea that one can distinguish such traits in anyone, with characters revealing the dangers within themselves. I received a digital copy of this fantastic novel from the author for an honest review.

In Brazil, Nazi fugitive Klaus Holland, aka Matheus Esperanca, raises his son by a prostitute with a Jewish kapo from Udenspul, the concentration camp he commanded. The son, Deus, considers the kapo his mother, and after her death, takes mysterious photos from her to a professor in his US university to research his ancestry, where he learns the true identity of his father and the extent of his crimes. Olokita brilliantly uses the concept of god as a measurement of morality, or rather lack of humanity, as Klaus plays God in determining who dies, though his own religious beliefs remain deliciously ambiguous. The character development is so well done that dear reader will be researching names. Although written in third person for everyone else, Klaus is in first person, bringing the reader up close and personal to a man with his own version of right and wrong based on his complete lack of empathy, exploring the idea of how powerful he believes himself. The ending revelation is quite coincidental and is evidenced only by Klaus’ perception, so it’s not clear why it’s readily believed by Deus and his new love Heidi. It’s anti-climactic after the delightful irony of Klaus’ downfall. With so many rumors, legends, and news items, inspiring a plethora of literature, on the Holocaust, this unique story of a fugitive hiding out in South America is a definite must-read. It’s themes rove beyond the simple good vs. evil and the idea that one can distinguish such traits in anyone, with characters revealing the dangers within themselves. I received a digital copy of this fantastic novel from the author for an honest review.

All posts by laelbr5_wp

Life Among Giants by Bill Roorbach

At 17, David witnesses his father’s public assassination for turning state’s witness, his mother collateral damage, his life spared due to spent ammo. He spends decades piecing together evidence to determine the killer’s identity, all while living his life as an NFL quarterback for the Dolphins, a random lover of the famous dancer Sylphide (who lives across the pond from his childhood home) and her protege Emily—introduced by him, and a restaurateur. His sister parcels out relevant information on rare occasions, spending her grief-stricken adulthood playing professional tennis, fighting mental illness, and searching for her parent’s killer against her boyfriend’s pragmatic advice. As Sylphide moves in and out of David’s life, secrets come unmoored and land at his feet every so often. Roorbach has built a fine cast of complex and extraordinary characters, nuanced to the hilt, integrity intact throughout the novel, all maddeningly non-forthcoming for page-turning tension. It can be awkward to follow the timeline back and forth, and David’s discoveries can be out of sync, as when he realizes his sister’s major secret years after his parent’s demise, and then in a following flashback is explicitly told the secret by his sister herself. No opportunity is missed to reference Emily as “the negress”—was that even used as late as the 70s and into the 80s? Her parents could have been a bit more rounded out as individuals instead of representations. These few distractions don’t detract from a unique story with an intriguing storyline and intense meta sex scenes. Roorbach is almost his own genre. He’s the Mainer Carl Hiassen in his dedication to untangling and tying up multiple storylines and presenting humans in all their glory and warts.

At 17, David witnesses his father’s public assassination for turning state’s witness, his mother collateral damage, his life spared due to spent ammo. He spends decades piecing together evidence to determine the killer’s identity, all while living his life as an NFL quarterback for the Dolphins, a random lover of the famous dancer Sylphide (who lives across the pond from his childhood home) and her protege Emily—introduced by him, and a restaurateur. His sister parcels out relevant information on rare occasions, spending her grief-stricken adulthood playing professional tennis, fighting mental illness, and searching for her parent’s killer against her boyfriend’s pragmatic advice. As Sylphide moves in and out of David’s life, secrets come unmoored and land at his feet every so often. Roorbach has built a fine cast of complex and extraordinary characters, nuanced to the hilt, integrity intact throughout the novel, all maddeningly non-forthcoming for page-turning tension. It can be awkward to follow the timeline back and forth, and David’s discoveries can be out of sync, as when he realizes his sister’s major secret years after his parent’s demise, and then in a following flashback is explicitly told the secret by his sister herself. No opportunity is missed to reference Emily as “the negress”—was that even used as late as the 70s and into the 80s? Her parents could have been a bit more rounded out as individuals instead of representations. These few distractions don’t detract from a unique story with an intriguing storyline and intense meta sex scenes. Roorbach is almost his own genre. He’s the Mainer Carl Hiassen in his dedication to untangling and tying up multiple storylines and presenting humans in all their glory and warts.

Flash Fiction Friday: delving into the past to fill out the rest of the year

rattle rattle rattle

we waited for a dark and stormy night to trespass

a little shed behind overgrown brush

passed every day on the way to work

turned out to be a tiny house

lightning served as our flashlight

kudzu blocked every window and door

we leaned onto the vines and broke through

inside the air was still

belying the wind whistling past

rattle rattle rattle

hush i whisper-screamed

it wasn’t me

rattle rattle rattle

i swear to zeus it wasn’t me

it had to be

frantic voice his

frantic voice mine

rattle rattle rattle

footsteps his

footsteps mine

centered in the room

waiting for lightning

listening

rattle rattle rattle

directly under us

curiosity stronger than fear

lightning startled

tension ignited

jumping back

a board flipped up

he’d found a hiding place

throwing the board aside

peering through the dark

lightning showed us bones

we gasped

we hopped up

bones

whose bones

why bones

why bones here

we have to tell the police

he snatched me back

we’ll have to confess to trespassing

yes we will

let’s go

wait

is there another way

rattle rattle rattle

no

i dragged him to the police station

we confessed

we professed

statements were made

suspicions aroused

dawn

weary of inquisition

rattle rattle rattle

you hear that sarge

i’m going to say no

come on did you hear that

i’m not going to say no

im not going to say yes

they took us in separate cars

to the tiny house reclaimed by nature

broken kudzu corroborated our story

the opening in the center of the room

looking down at the bones

we see now that they are child size

we are hustled out and returned to the station

where we await news and consequences

together in a small interrogation room

hours pass

lunch is brought

more hours pass

sarge returns

you guys can go

we go

unfulfilled

such a mystery

will they tell us

two days pass

sarge calls us

please come to the station

we come

sit in sarge’s dark crowded office

he shows us a photo of a blonde girl maybe 5

you found her bones

missing 5 years

a year missing for each one alive

rattle rattle rattle

i didn’t hear that

sarge says

we did

on the way home we talk to her

rattle rattle rattle

you’re welcome

Sandi Ward—women’s fiction author who writes humanity-embracing stories from the unique perspective of cats

I met Sandi on Twitter. She is super friendly and supportive of other writers. If you’re a fan of Hallmark, love heartwarming stories, and appreciate learning about other humans through reading, her novels are for you. Oh, you must also love cats! Here’s my review on her second novel Something Worth Saving.

Tell me about your writing process: schedule, environment, strategies, and inspirations tangible and abstract—what’s in your office?

Tell me about your writing process: schedule, environment, strategies, and inspirations tangible and abstract—what’s in your office?

Because I work full-time (I’m a medical copywriter at an ad agency), I write my fiction sporadically, whenever I can grab a few minutes here and there. My MacBook Air is always with me, and it essentially is my office-to-go! I’ll write in the early morning, on my lunch hour, late at night, or whenever else I can grab a few minutes.

I prefer to write with a hot cup of coffee nearby. My primary requirement is quiet. I can’t write with music or other background noise going on.

I don’t outline my story arc on a line chart, or put plot points on post-it notes, or anything like that. I’m completely what some people call a “pantser,” making it up as I go along (flying by the seat of my pants). I re-read written chapters and then add a new one, going back constantly to edit in new ideas. My goal is to write stories that are unexpected, and not formulaic. I let the characters surprise me, in the hopes that they will also surprise the reader.

Walk me through your publishing process from final draft to final product: publishing team, timeline, and expectations of you as the author, especially toward marketing and publicity.

Walk me through your publishing process from final draft to final product: publishing team, timeline, and expectations of you as the author, especially toward marketing and publicity.

Kensington gives me a year to write a novel, during which time their art department starts to design a cover and their marketing team writes potential cover copy (once I can supply a synopsis). Once the draft is done, it goes to my agent and editor, and we do a round of changes before moving on to copy editing, and finally page proofs. This stage also takes about a year, from final first draft to published book.

On the one hand, this process is slow. By the time of book launch, it has been over a year since I wrote the story. But I’m happy to be writing general fiction, where I get the time I need to devote to writing a first draft. Other writers, in genres like romance and mystery, are sometimes under pressure to write much faster, and that would be tough for me. I’m always promoting books at the same time I’m writing new stories, so I’ve got plenty to keep me busy. Right now I’m finishing up the first draft of my third novel, What Holds Us Together.

My publicists and the social media team at Kensington decide where and how to promote the book, for example via print or online advertising, but I also do as much as I can! I maintain my website and social media accounts, and reach out to other authors, readers and book bloggers who might be able to share news and reviews of the book.

Describe your support system online and IRL—who are your biggest cheerleaders?

My literary agent, Stacy Testa at Writers House, is my #1 go-to person for all of the questions I have about writing and promotion. She’s amazing and I’m very lucky to be working with her!

Other authors have also been incredibly supportive. The online writing and reading community is great about sharing information and helpful tips. I belong to a number of writing-based Facebook groups where I learn new things every day, and try to share some of my own knowledge.

At home, it helps that my husband and teens are all writers. My husband is also in advertising, my son is a journalism major in college, and my daughter is a student filmmaker. They can relate when I need to disappear into my laptop for a while.

Your unusual protagonists are cats; I suspect you’re a huge animal lover, and I’m curious how you determined to write cat main characters. How does your life influence your writing and vice versa?

I do love animals! I have both a cat and a dog.

When people ask me what inspired me to write from a cat’s point of view, the truth is, I don’t remember exactly how I got started with it. Essentially, I wanted to experiment and try writing from the viewpoint of an unconventional narrator. I love books like The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time and The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, which are written from unexpected points of view, where the reader realizes that more is going on than the narrator fully understands.

A main theme that runs throughout all of my books is how hard it is to be a parent—especially of teenagers. Real life absolutely influences my characters and stories. I don’t usually talk about my personal life too much, but if you read my books, you’ll quickly figure out where I stand on many issues.

When I wrote Something Worth Saving, I was feeling pessimistic about how divisive society has become. I don’t have all the answers. I think it’s okay to disagree with others, but it’s also important to be respectful and not make anyone feel unsafe. My character Charlie (my narrator Lily’s favorite human) should not have to feel threatened when he wants to express himself—not at school, not at home, not anywhere. For me, writing a novel is a better way to try and convince someone to take another look at an issue, rather than shouting on Twitter about it.

What do you love most about your creativity?

I enjoy getting really enthusiastic about ideas, words and images. This is true at my job at the ad agency as well as when I’m writing fiction. Great ideas should get the creator fired up, and want to share those thoughts with the world. I believe you have to write for yourself first, and then you can try to get everyone else on board.

Connect with Sandi:

The Bean Trees by Barbara Kingsolver

Marietta left Kentucky after high school, changed her name to Taylor, and become a mother through an unexpected incident, ending up in Tucson with a single mother roommate and a job as a tire mechanic for a woman who rescues undocumented immigrants. Selectively mute from obvious chronic abuse, her newly acquired daughter Turtle learns to trust Taylor, who learns to trust in her new friendships as she seeks a way to keep Turtle legally and build their life in Tucson.

Marietta left Kentucky after high school, changed her name to Taylor, and become a mother through an unexpected incident, ending up in Tucson with a single mother roommate and a job as a tire mechanic for a woman who rescues undocumented immigrants. Selectively mute from obvious chronic abuse, her newly acquired daughter Turtle learns to trust Taylor, who learns to trust in her new friendships as she seeks a way to keep Turtle legally and build their life in Tucson.

Kingsolver carefully details a young woman’s journey to find herself, taking everything that comes at her and building a valuable life with it all. She’s brilliant at showing the depth of Marietta’s mother’s love at letting her daughter go and make her own decisions, including changing the name her mother gave her, and Taylor’s love in her determination to keep the daughter who was literally handed to her.

Fans of Willa Cather, Celeste Ng, and Elizabeth Strout will appreciate this novel and Kingsolver.

Something Worth Saving by Sandi Ward—pub date December 18, 2018

Lily loves Charlie more than any other human, for he rescued her when other potential adopters frowned at her limp. She’d been abused by her previous owner and her broken leg healed without veterinarian intervention. Now he’s being bullied and Lily must figure out a way to help him amid the chaos of Dad’s drinking, Mom’s sadness, his sister’s possible suspect boyfriend, and his big brother’s anger. The unique perspective of a cat gives readers a view from inside the family, but with a pure, some might say naive, but definitely less than jaded, outlook. Lily can be as surprised as a person by such things as Charlie’s choice of “mate” being another boy. Ward’s representation of a gender-fluid, gay teenager comes across as natural and inclusive, even as she shows the challenges he must face, especially from his own family. His mother and sister’s acceptance counter his father’s confusion and his brother’s resistance. Of course there’s a romantic interest for mom, who’s separated from dad and planning divorce. However, he immediately touches her intimately and insinuates himself into family issues, coming across as a bit creepy rather than romantic—too much too soon. This is the only part of the story that doesn’t flow organically, a small distraction. This story presents multiple serious subjects that are handled with compassion: alcoholism, addiction, chronic pain, divorce, and gender expectations. Ward takes her family down a path of resolution surprising, yet realistic. Readers who love main characters off the beaten path will appreciate this story; animal lovers will be vindicated.

Lily loves Charlie more than any other human, for he rescued her when other potential adopters frowned at her limp. She’d been abused by her previous owner and her broken leg healed without veterinarian intervention. Now he’s being bullied and Lily must figure out a way to help him amid the chaos of Dad’s drinking, Mom’s sadness, his sister’s possible suspect boyfriend, and his big brother’s anger. The unique perspective of a cat gives readers a view from inside the family, but with a pure, some might say naive, but definitely less than jaded, outlook. Lily can be as surprised as a person by such things as Charlie’s choice of “mate” being another boy. Ward’s representation of a gender-fluid, gay teenager comes across as natural and inclusive, even as she shows the challenges he must face, especially from his own family. His mother and sister’s acceptance counter his father’s confusion and his brother’s resistance. Of course there’s a romantic interest for mom, who’s separated from dad and planning divorce. However, he immediately touches her intimately and insinuates himself into family issues, coming across as a bit creepy rather than romantic—too much too soon. This is the only part of the story that doesn’t flow organically, a small distraction. This story presents multiple serious subjects that are handled with compassion: alcoholism, addiction, chronic pain, divorce, and gender expectations. Ward takes her family down a path of resolution surprising, yet realistic. Readers who love main characters off the beaten path will appreciate this story; animal lovers will be vindicated.

Flash Fiction Friday: delving into the past to fill out the rest of the year

Questions Live On

A lithe, unassuming young girl walks down her street. She sees a dirty old man who grabs at her skirt. Bastard! They never grow out of it. She sees a man giving flowers to a woman on her doorstep. Sweet, but sure it’s only surface sugar. She sees a starving artist painting picnickers in the park. He doesn’t know from angst. She sees a boy smacking his dog for disobeying. He won’t grow out of that either. She sees a military-uniformed man on a park bench, much-loved letters scrunched in his hand, staring into space. She feels no sympathy.

They are all her father. His art, his military service, not even his love for her mother, compensates for making her feel dirty, and forcing her to live in the dark end of the tunnel, at 14. Her mother was lost to her, just a woman at the other end of that tunnel who regulated her day. Feeding and clothing must equal love, or is it merely obligation? Would love allow pain to continue, and knowledge of it to slip into fog? A drowning man can’t save a drowning man. A woman in pain cannot save a girl in pain.

Look to God then. Such a small prayer over and over for lightning to strike him down. God brought him back from war. War! So much more convenient than lightning. Keep your God! My mother will not become a person, for God’s sake.

The quiet young man of 15 writes poetry for her; she refuses flowers. She wonders if he lies. He says everyone does. He lies? She wonders if he ever could be guilty of her father’s sin. This question remains unasked. He touches her face. She flinches. He cries at night for her.

He writes:

Blue skies

Blue eyes

So big they take you in

The Blond flows long

Forget the pain

Sadness dies

For you so sweet

Dreams are real

Dreams are true

Everyone lies

Not you

For you believe

That Truth one day

Will make people

Bigger than they are

Ideals die hard

Love remains

Despite experience.

Her diary reads:

Cliché — understanding or manipulation? If I did not believe that one day my life will be elsewhere, courage would fail me to continue life. Yet, I’m allergic to pain — hah!

Even the screaming, the touching, and the nonsense cannot belie the fact that I was meant for greater things. If hardship builds character, then I am indeed of great character. I just hope it’s not a cartoon character, and God is not a comedian.

Tuesday, she meets a Jewish man, who explains to her that Jesus was just a man, a great prophet, maybe, but a simple mortal nonetheless. She meditates on this for two days before belief settles in. Thursday, she meets a philosopher, who expounds upon Plato’s shades of gray. Nothing is real. It is all perception. In one afternoon, conviction of Plato’s theory solidifies in her mind. Friday, she meets an old woman who outlines men’s evils. Her father’s sin makes the list. Such a sweet young thing should not have to live in a world of such men. The old woman’s revelation brings her no comfort.

Her father comes to her Saturday. Sunday, to spite God, she steps in front of a bus. Her parents weep, but the young man grieves dry-eyed, knowing the Truth.

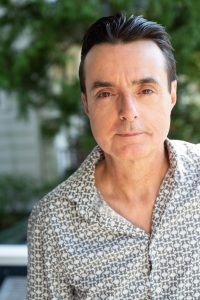

Mark Dery—Author, Biographer, Essayist

Mark promoted his Edward Gorey biography Born to Be Posthumous on Twitter and I politely asked for a copy to review. He graciously offered publisher contact information, and Little, Brown, & Company sent me a copy. It’s so good, people. If you’re not familiar with Gorey’s work, you will want to be in on this open secret after reading Dery’s book. Gorey was a fascinating character, and Dery is a brilliant storyteller. He’s really so much more—this interview a tiny peek into the profundity of his work, but I’ll let you read up on Mark further on his own website. Links to connect with Mark and purchase his work follow the interview.

Mark promoted his Edward Gorey biography Born to Be Posthumous on Twitter and I politely asked for a copy to review. He graciously offered publisher contact information, and Little, Brown, & Company sent me a copy. It’s so good, people. If you’re not familiar with Gorey’s work, you will want to be in on this open secret after reading Dery’s book. Gorey was a fascinating character, and Dery is a brilliant storyteller. He’s really so much more—this interview a tiny peek into the profundity of his work, but I’ll let you read up on Mark further on his own website. Links to connect with Mark and purchase his work follow the interview.

Tell me about your writing process: schedule, environment, strategies, inspirations intangible and material, magic spells, etc.

Tell me about your writing process: schedule, environment, strategies, inspirations intangible and material, magic spells, etc.

I rise at the crack of noon, as Christopher Hitchens liked to say, and lower myself into a vat of virgins’ blood in strict adherence to Elizabeth Báthory’s beauty regimen for eternal youth. After a rejuvenating soak, I trim the topiary; then spend the morning in bed, languidly leafing through the Encyclopedia of Unimaginable Customs and nibbling candied violets.

But seriously: I have no set schedule unless I’m on assignment—working on a lecture, knocking off a piece of journalism, or writing a book, as I have been for the past seven years.

My “environment”—why am I thinking of a hermit crab in a terrarium?—is a small office in the attic of my house, a worse-for-wear 1868 Victorian in New York’s Lower Hudson Valley. It’s the proverbial garret, snug as a fo’c’sle, or what I imagine a fo’c’sle would feel like, based on second-grade memories of books about pirates and whaling. On top of one of my bookshelves is what I like to call my aesthete’s altar, a poor man’s cabinet of curiosities: a pickled Jerusalem Cricket floating in formalin, a desiccated Tarantula Hawk, postcards of my pantheon of secular saints—E.A. Poe, Oscar Wilde—and of images from my personal symbology (Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley, that Diane Arbus photo of identical twins) and, for crowning effect, two human skulls. Which makes it sound more romantic than it is: the paint on the walls nearest my desk is scabrous; teetering stacks of whatever books I’m using for my research are heaped on every available surface, including the floor surrounding my desk, which makes the passage from desk to door tricky at best and perilous at worst. When I’m in the death throes of an essay or a book chapter, things can get seriously out of hand, with xeroxes of articles and books propped open to specific pages threatening to avalanche off my desk, which they often do. Inspiration? That comes from the subject at hand, whatever it is, but if inspiration is lacking, a heart-hammering cup of Bustelo—three scoops of espresso made in my battle-tested Bialetti Moka—never fails to beckon the muse. I’m one of those writers who listens to music while he works, instrumental only (words are too distracting), preferably something that suits the mood of whatever I’m working on, though not necessarily in a strictly literal way. For Gorey, that could be anything from Morton Feldman to Jóhann Jóhannsson’s soundtrack for Arrival to György Ligeti’s “Études for Piano” to No Pussyfooting by Fripp and Eno. By five o’clock, I’ve had two pots of Bustelo and need to chase the evil spirits out of my head. A bike ride or a run along the tree-lined streets at the woodsier end of town are just what the doctor ordered; deer are everywhere, browsing on suburban shrubs, and the trees look uncanny in the oncoming twilight, branches clawing at the sky. (My iPhone is full of photos of trees that look like something out of Algernon Blackwood’s gothic tales of haunted forests.) Then it’s home for dinner, typically spent yelling at cable news, then back to my lair for a few hundred more hard-won words, with a glass of shiraz to downshift after my heavily caffeinated day.

How do you choose your subjects?

How do you choose your subjects?

They choose me. I have the attention span of a gnat, which is good for the mind but bad for the wallet, since hoeing the same row is more lucrative than being an intellectual flâneur. One subject leads me to another, through some combination of serendipity and free-association. In an age of hyperspecialization, being a generalist isn’t a recipe for success but the idea of fitting your mind to a monorail seems like living death. I had a colleague once, a journalism pundit, who told an interviewer (with suitable portentousness), “I get up every day and ask myself one question: What are journalists for?” Just shoot me, I thought.

Talk about your support system online and IRL; what motivates you? Who are your biggest cheerleaders?

Talk about your support system online and IRL; what motivates you? Who are your biggest cheerleaders?

In all honesty, I don’t look for support, at least not in the sense you seem to mean—a kind of validation. Do most writers? I suspect not. Writers write not because they want to write but because they must; it’s not what they do but who they are. Certainly, fan mail is balm to the soul, not to mention a bracing antidote to that nasty review that made you want to inch out onto the window ledge—or drop a cornice on the offending critic. That said, I write for The Ideal Reader, a vaguely defined apparition who should never be brought into sharp focus but who bears a striking resemblance, I have a sneaking suspicion, to the face in the shaving mirror. Few writers admit it, but most write for themselves. Of course, you have to divide yourself by The Other—your wider audience—to save yourself from a fatal self-indulgence, not to mention abject poverty, which is where editors are very writer’s saving grace. Mine, Michael Szczerban at Little, Brown, saved me from a million little misdemeanors and a few Class A felonies in my Gorey biography. Writing is a communicative act, to be sure, unless you’re writing a diary, the point of which has always eluded me: there’s no paycheck, and no applause. At the same time, a good writer is his own severest critic and thus his most honest reader—maybe not the only support system he needs, but certainly the linchpin of the thing. As Lou Reed snarls in his onstage rant, on Take No Prisoners, about the rock critic John Rockwell, “I don’t need you to tell me that I’m good.”

As a writer and public speaker, how does your life influence your work and vice versa?

As a writer and public speaker, how does your life influence your work and vice versa?

It doesn’t. Lecturing is to writing as improvisation is to composing, I suppose. I speak from written texts but, in the run-up to my talk, annotate them with frantically scribbled marginalia, jotted notes for fruitful digressions inspired by keywords in the text. They’re a kind of musical notation, indicating where to wander off into the weeds and when to double back to the main arc of the argument or narrative. Sometimes, ideas generated in this manner will find their way into a revised version of the essay or book chapter or whatever it is; so, too, will comments and questions from the audience. But I’m enough of a control freak that I almost never speak completely extempore. At the same time, I’d never think of just reading my text, as academics tend to; it’s pure chloroform, calculated to send the audience streaming to the exits in the first 10 minutes!

What do you love most about your creativity?

What do you love most about your creativity?

That it opens the door to The Marvelous, as the surrealists called it. As a practicing surrealist, I’m always on the lookout for The Marvelous—the uncanny, the fantastic, the utterly alien lurking just around the corner, hidden in the everyday, but only revealed when seen from a certain angle. Gorey was fond of quoting two quotes that were, he said, at the heart of his worldview. One of them was from the surrealist poet Paul Éluard: “There is another world but it is this one.” The other was from the Oulipo author Raymond Queneau: “Things aren’t as they seem, but they aren’t anything else, either” (or words to that effect). Where those two realities flow together is where I fish, as a writer.

Connect with Mark:

Connect with Mark:

Gardenland by Jennifer Wren Atkinson

This book is more than expected, with historical references, how gardening has morphed into a recreational activity in our industrial age, advances in gardening—for sustenance and pleasure, and a chronology of gardening literature. It’s about far more than planting, encompassing various philosophies and exploring gardening throughout fiction and non-fiction. I was fortunate to receive this wonderful book about the practicalities, aesthetics, and dreams of gardening from the publisher through NetGalley.

This book is more than expected, with historical references, how gardening has morphed into a recreational activity in our industrial age, advances in gardening—for sustenance and pleasure, and a chronology of gardening literature. It’s about far more than planting, encompassing various philosophies and exploring gardening throughout fiction and non-fiction. I was fortunate to receive this wonderful book about the practicalities, aesthetics, and dreams of gardening from the publisher through NetGalley.

The Girl of the Lake by Bill Roorbach

This collection opens with a tale so convincing dear reader will be googling Count Darlotsoff of the Russian Revolution. Roorbach’s stories ramble along pleasantly, with wit and wisdom, from a unique perspective. Then BOOM! Something astonishing happens, sometimes indicated by a simple line, “And fell into a basement hole,” and sometimes portraying a much larger concept, such as patricide. The tales delve into history—the aforementioned Russian Revolution; plunges deep into socio-political culture—“His father was an important king or chieftain in an area of central Africa he refused to call a country, an area upon which the Belgians and several other European powers had long imposed borders and were now instituting ‘native’ parliaments before departing per treaty after generations of brutal occupation;” and parses human emotions and relationship dynamics—“sharks unto minnows.” There’s even a ghost story, with elements of land conservation, familial squabbles, and burgeoning love. As diverse as the themes are, and as broad the representation of people, one story stands out for its LGBT ignorance, as a main character tells the benefactor of her theater, a widower asking for a kiss, “Marcia had politely allowed just one, then explained that while being a lesbian might not mean she was entirely unavailable, her long-term relationship did.” He then proceeds to win over her wife, and they merrily cavort about town, all three holding hands, doing everything as a threesome. Lesbian relationships are real relationships, and lesbians are not toys for a man’s pleasure. That being said, this is a blemish on a set of otherwise fascinating and weird and brilliant stories. The book is dedicated to Jim Harrison, whose fans will likely appreciate Roorbach’s work.

This collection opens with a tale so convincing dear reader will be googling Count Darlotsoff of the Russian Revolution. Roorbach’s stories ramble along pleasantly, with wit and wisdom, from a unique perspective. Then BOOM! Something astonishing happens, sometimes indicated by a simple line, “And fell into a basement hole,” and sometimes portraying a much larger concept, such as patricide. The tales delve into history—the aforementioned Russian Revolution; plunges deep into socio-political culture—“His father was an important king or chieftain in an area of central Africa he refused to call a country, an area upon which the Belgians and several other European powers had long imposed borders and were now instituting ‘native’ parliaments before departing per treaty after generations of brutal occupation;” and parses human emotions and relationship dynamics—“sharks unto minnows.” There’s even a ghost story, with elements of land conservation, familial squabbles, and burgeoning love. As diverse as the themes are, and as broad the representation of people, one story stands out for its LGBT ignorance, as a main character tells the benefactor of her theater, a widower asking for a kiss, “Marcia had politely allowed just one, then explained that while being a lesbian might not mean she was entirely unavailable, her long-term relationship did.” He then proceeds to win over her wife, and they merrily cavort about town, all three holding hands, doing everything as a threesome. Lesbian relationships are real relationships, and lesbians are not toys for a man’s pleasure. That being said, this is a blemish on a set of otherwise fascinating and weird and brilliant stories. The book is dedicated to Jim Harrison, whose fans will likely appreciate Roorbach’s work.